This week saw comments close on the Western Cape Government’s (WCG) draft Inclusionary Housing Policy Framework. However, as the property development and construction sector await the next round in the process, as well as the first draft of the City of Cape Town’s own inclusionary housing policy, many developers and other professionals in the industry have expressed their doubts as to whether government truly has a practical understanding of the property industry and the complexities faced on a daily basis.

One of the organisations that have delivered comment on the WCG’s inclusionary housing policy is the Western Cape Property Development Forum (WCPDF), an organisation that has been actively engaging with various public and private roleplayers on the topic since 2018. Yet the organisation’s members – drawn from the full spectrum of y professionals involved in the production of property – are concerned that, to date, all inputs and practical considerations raised by the industry have either been misunderstood or fallen on deaf ears.

Government’s own failures to address spatial injustice

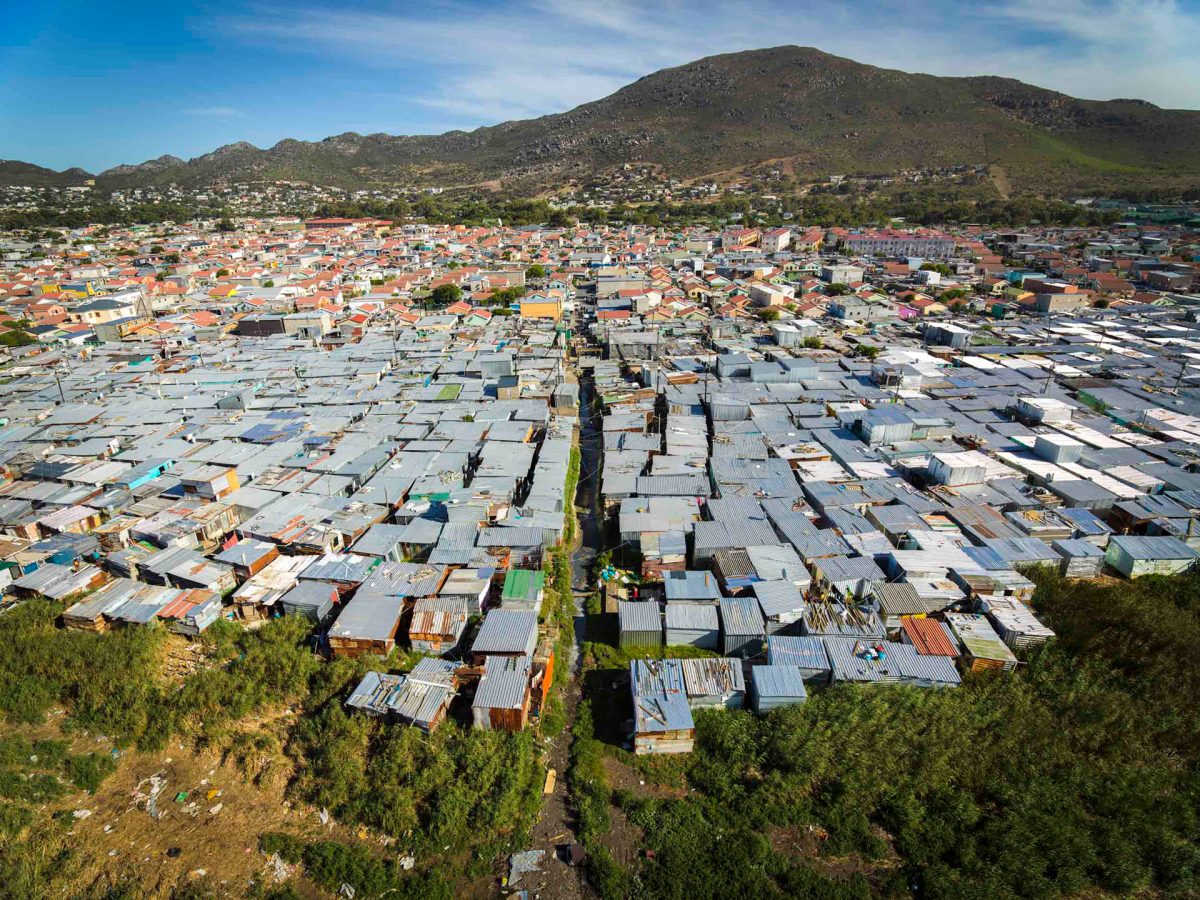

According to WCPDF chairperson, Deon van Zyl: “Our organisation has always supported the principle that all people have a right to well-located accommodation that brings them closer to economic activity and addresses the spatial injustices of the past.

“However, we oppose the principle that the private sector should be taxed with the task of addressing these spatial injustices when it is clear that all three spheres of government have failed in their own mandates to transform the historic injustices within South African cities.”

Three critical issues exist for the WCPDF in this regard, says Van Zyl: “Top of the list is government’s ongoing failure to release well-located urban land that could be used for affordable or inclusionary housing in the first place.

“Then there is the failure to facilitate the development of new economic nodes in previously disadvantaged areas and, finally, a fundamental failure to develop viable, affordable public transportation systems that would link people from where they currently live to economic opportunities.”

Van Zyl refers to these as the “elephants in the room” which government refuses to acknowledge, and which will only result in a policy framework that cannot be taken seriously: “The fact that a topic of this magnitude is addressed in isolation and not in an integrated, holistic economic growth strategy confirms the intent of government to shift its social and constitutional obligations onto the private sector.”

Among the WCPDF’s concerns around the policies being formulated (including the City of Cape Town’s, yet to be released although already more than four years in the making), is that they’re reactive rather than proactive, and were it not for the efforts of activist groups would never have seen the light of day.

Notes Van Zyl: “It must be acknowledged that organisations such as Ndifuna Ukwazi and GroundUp very successfully launched Western Cape and Cape Town-focused legal and media campaigns on the topic. What we are therefore witnessing is a reaction to a these campaigns, rather than local or provincial government taking a proactive lead in responding to the goals and aims of the Constitution.”

Another tax on an over-taxed industry

With the property development and construction sector being one of the largest employers in South Africa (second only to mining), it is responsible for placing much-needed wages into the pockets of some of the poorest communities in South Africa. However, this sector – and by implication, it beneficiaries – are subjected to ever-increasing legislation, policies, regulations and taxes that ultimately also have a direct inflationary impact on the end users of its products.

The introduction of inclusionary housing-related offsets on new developments, as proposed by the Western Cape Government’s policy framework and as expected to be seen in the City of Cape Town’s own policy, are being viewed by industry members as being nothing more than yet another tax.

Van Zyl explains: “The point of departure on the inclusionary housing policy framework is the concept of land value capture (LVC), whereby government is the owner of the development rights on a particular piece of land on behalf of society. The release of such rights to the private sector will come in the form of a levy to be paid by the developer and the cost passed onto the end user and market in general.”

The policy spends some time arguing that the concept of LVC is not a tax even though tax is defined as: a compulsory contribution to state revenue, levied by the government (Oxford English Dictionary). In the policy framework, payment of cash taxes is replaced with “payment in-kind”.

Adds Van Zyl: “If not a tax, then the granting of rights in lieu of payment would equate to the selling of development rights, which is not allowed in legislation. We must therefore give the benefit of the doubt to the drafters that it is not their intention to equate LVC as a sales transaction; however, the only alternative description for the concept of LVC can therefore be that it is a taxation on property development, which ultimately increases costs to the open market’s tenants or purchasers of residential property.”

Paying for efficiencies which government should already be delivering

“As if these weren’t enough,” says Van Zyl, “our sector is encumbered by extreme inefficiencies in government which, on the one hand, is incapable of proactively creating infrastructure capacities while on the other suffers from an inability to process the plethora of statutory applications preceding any fixed capital investment.”

Another factor contained in the WCG’s policy draft is that processes governing the property development industry will be improved for those developers willing to partner with the province – in other words, become more efficient. On this Van Zyl comments: “The mere fact that such a promise is tabled is an acknowledgement that inefficient processes currently undermine investment; perhaps the most constructive self-criticism by government.”

The WCPDF’s response to the policy suggests that government should rather understand the unique characteristics that the private sector has to offer in terms of innovation, delivery emphasis in lieu of profits, access to capital and managerial skills.

“Government should seek to co-opt these private sector skills and resources to fill the gap left by government’s own nature and characteristics,” says Van Zyl. “Only when government understands the contribution and qualities of the private sector can it start to consider the roles and responsibilities of a partnership relationship. Van Zyl adds: “We are also concerned that the minuscule contribution that this policy framework will generate in new housing opportunities speaks to the fact that, at best, the policy as it currently stands will lead to no more than lip service or political window dressing and, at worst, will simply maintain the status quo of spatial injustice.”

The proposed solution

In its current form, as read by WCPDF, the draft Inclusionary housing policy framework does not guide local authorities to deal with the topic in an integrated and holistic way.“The only way forward,” says Van Zyl, “is to go back to the drawing board with a four-phase approach that should be the guiding principle in any policy framework document of this kind.”

The approach recommended by the WCPDF

- Lead by example: the WCPDF calls on government to commit to releasing state-owned land either directly or in partnership with the private sector, specifically earmarked for affordable housing.

- Explore relationships between employers and employees: the opportunity exists for employers to engage on behalf of their employees and provide bridging funding or surety for employees to enter the formal housing sector. In this instance, the use of well-located public-sector land at subsidised rates will be critical.

- Incentivise rather than tax the private sector: in other words, encourage this sector of its own accord to provide inclusionary housing (ie: through tax rebates and financial incentives).

- And only then, when all else fails and as a last resort: tax the private sector.

Concludes Van Zyl: “As the WCPDF, we reiterate that our organisation is not opposed to the concept of inclusionary housing, but it is fundamentally opposed to the concept of taxation when alternative funding options are patently clear.

“Our members remain committed to the concept and we repeat our offer to work with government to identify and strategise on methods by which quality and effective inclusionary housing can be delivered. This will however require a fundamental mind shift on behalf of all parties and will require the type of innovative thinking that has not yet been placed on the table.”

More news

- STATE-DRIVEN OPPORTUNITIES FOR SA CONSTRUCTION COMPANIES BUT MANAGING RISK IS A PRIORITY

- PART 4: SA’S TRADE DILEMMA: A PODCAST DISCUSSION WITH DONALD MACKAY

- CONCOR KICKS OFF OXFORD PARKS BLOCK 2A PHASE I PROJECT

- PART 3: SA’S TRADE DILEMMA: A PODCAST DISCUSSION WITH DONALD MACKAY

- MBA: ‘HOW CONSTRUCTION FIRMS SHOULD PREPARE FOR THE WORST’